JE16: Auxiliary equations and tests of local DG scheme for advection-diffusion equations¶

The local DG scheme can be used to solve equations with diffusion terms. This is achieved by replacing the second order terms in the original system with first order terms. This leads to a system of first order equations which can then be updated with the standard DG algorithm.

Gkeyll has an arbitrary dimensional nodal DG updater that can be used to solve such equations. The basic idea is to pass extra fields as auxiliary variables. This allows a very general scheme in which several different types of equations can be solved. In this document I test the nodal DG updater and use the auxiliary variables framework to solve a number of problems, including those with diffusion.

Auxiliary variables for solving 2D advection equations¶

In the journal entry JE12 the Poisson bracket updater is tested with passive advection in a 2D flow field given by \(u_x = \partial \psi/ \partial y\) and \(u_y = -\partial \psi/ \partial x\), where \(\psi\) is a specified potential. The same problems can also be solved with the nodal DG updater by specifying the flow velocity as an auxiliary variable. This allows tracing passive advection in a general flow field (i.e. not constrained to be incompressible or 2D). In this set of tests this ability is exercised by solving the 2D scalar advection equation

with specified flow field \(\mathbf{u}(x,y,t)\). Note that as the velocity field is specified explicitly and does not depend on the solution, it must be passed into the DG updater as an auxiliary variable. This requires creating extra fields and auxiliary equation objects and passing them to the nodal DG updater. See the script s201 for an example of how this is done in Gkeyll.

Rigid-body rotating flow¶

In this test a rigid body rotating flow is initialized as

which represents a counter-clockwise rigid body rotation about \((x_c,y_c)=(1/2,1/2)\) with period \(2\pi\). Hence, structures in \(f\) will perform a circular motion about \((x_c,y_c)\), returning to their original position at \(t=2\pi\).

The simulation was performed with with an initial cosine hump of the form

where

For this problem, \(r_0=0.2\) and \((x_0,y_0) = (1/4, 1/2)\). To test convergence, the simulation was run to \(t=2\pi\) with grid sizes \(16\times 16\), \(32\times 32\) and \(64\times 64\) grid (keeping time-step fixed). The results were compared to the initial condition and errors computed and are shown in the following table.

Cell size |

Average Error |

Order |

Simulation |

|---|---|---|---|

\(1/16\) |

\(1.8302\times 10^{-2}\) |

||

\(1/32\) |

\(5.0170\times 10^{-4}\) |

1.76 |

|

\(1/64\) |

\(1.0859\times 10^{-5}\) |

2.22 |

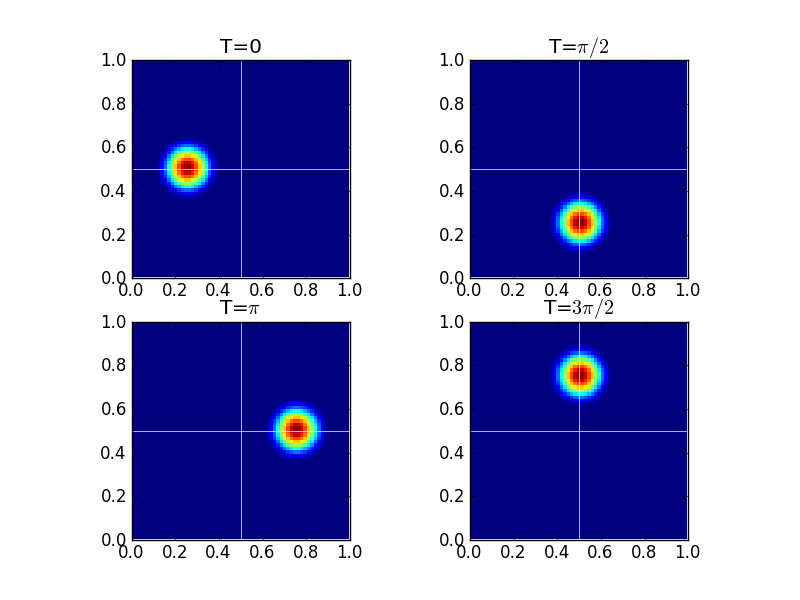

Next, a piecewise quadratic spatial scheme was used to compute the solution to \(t=4\pi\) on a \(32\times 32\) at which point the cosine hump has advected twice about the origin. The figure below shows the solution at four different times, indicating that the algorithm essentially advects the initial hump without any significant distortion.

Rigid-body rotation solution on a \(32\times 32\) grid using a piecewise quadratic discontinuous Galerkin scheme at different times [s204]. The white lines are the axes drawn through the point around which the flow rotates. These figures show that the scheme advects the initial cosine hump without significant distortion even on a relatively coarse grid.¶

Swirling flow¶

In this problem we use a time-dependent velocity field

This represents a swirling flow that distorts the vorticity field, reaching a maximum distortion at \(t=T/2\). At that point the flow reverses and the vorticity profile returns to its initial value.

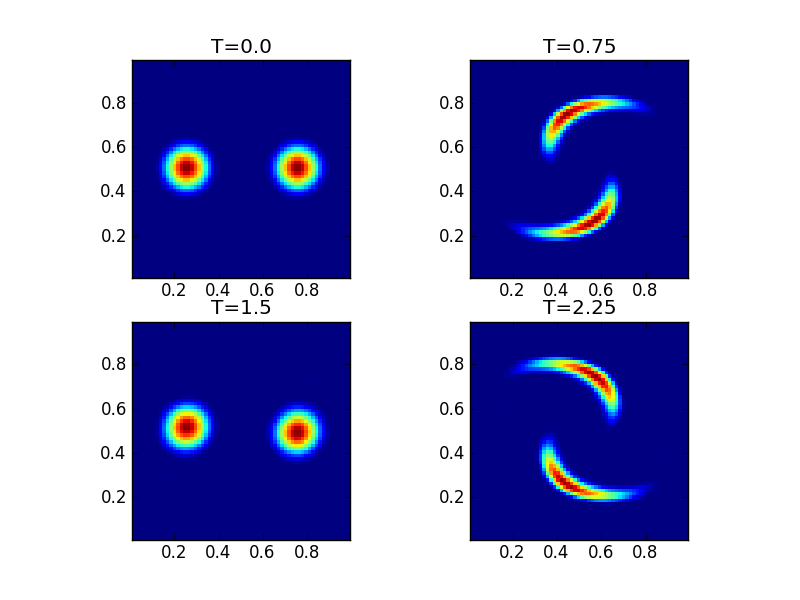

We use a piecewise quadratic scheme on a \(32\times 32\) grid and run the simulation to \(t=2T\). The results are show in the following figure.

Swirling flow solution on a \(32\times 32\) using a piecewise quadratic discontinuous Galerkin scheme at different times [s205]. The figure shows the initial condition, the maximum distortion in the first half period after which the solution returns to its initial value, swinging back for a second oscillation.¶

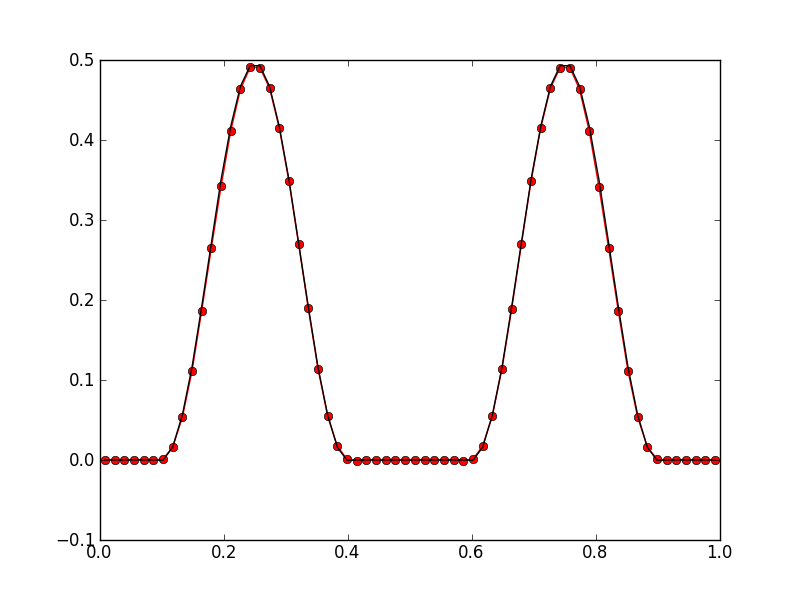

In the following figure compares the final solution to the initial conditions.

Swirling flow solution on a \(32\times 32\) grid using a piecewise quadratic order discontinuous Galerkin scheme at \(t=2T\) (red dots) compared to the initial conditions (black line). The algorithm is able to handle this complicated flow pattern and show very little distortion of the final solution. See [s205].¶

Local DG for advection-diffusion equation¶

The DG method can be used to solve equations that have a hyperbolic as well as a parabolic part. Consider first the advection-diffusion equation

where the constants \(a\) and \(D\) are the advection speed and the diffusion coefficient respectively. This can be rewritten as a system of first order equations

where \(g \equiv Df\). This system of two first-order equations can now be solved using the standard DG algorithm. The first paper to systematically study this local DG scheme, even though earlier uses had appeared for solving Navier-Stokes equations, was done by Cockburn and Shu [Cockburn1998].

Just as in the scalar case we need to compute a numerical flux at each cell interface. Let \(\mathbf{Q} \equiv [f, w]^T\) and \(\mathbf{F} \equiv [w, g]^T\). Then, the numerical flux at interface \(i+1/2\) can be written in the usual form as

where \((af)_{i+1/2}\) is a suitable flux for the hyperbolic term and \(c_{ij}\) are some coefficients. Different selectiions of these coefficients lead to different schemes with different stability and accuracy properties. Note that to obtain an explicit scheme we must set \(c_{22}=0\) to avoid coupling neighbor values of \(w\) leading to an implicit equation.

For a central scheme we simply put \(c_{ij} = 0\). With this choice one can show that for piecewise constant basis functions this leads to a five-point central difference formula for approximating the second derivatives

On the other hand, selecting \(c_{11} = 0\) and \(c_{12} = -1/2\) and \(c_{21} = D/2\) leads to (with piecewise constant basis functions) the usual three-point formula for approximating the second derivatives

Even though both choices lead to second-order accurate (for piecewise constant basis functions) approximations the latter is preferred as it avoids the odd-even decoupling of the solution. A more through analysis of the different numerical fluxes and their stability and accuracy properties is carried out in [Arnold2002] for the Poisson equation.

In the algorithm coded up in the Lua scripts, the second equation is first updated to compute \(w\) given the \(f^n\). These are then used to update the solution to give \(f^{n+1}\). Note that as the resulting scheme is explicit the time-step is limited by both the hyperbolic as well as the parabolic terms. Hence, it is possible that for a sufficiently fine grid and/or large values of the diffusion coefficients the time-step will have to be significantly smaller than that allowed by the advection speed.

We are initially focussing on cases where the collision frequency is very small so an explicit treatment should be sufficient. Extensions to an implicit method for higher collisionality may be considered later

To test the algorithms implemented in Gkeyll a series of tests were performed to check convergence. The simulations are initialized with \(f(x,0) = \sin(x)\) are run on a domain \([0,2\pi]\). The exact solution to this problem is given by

and is compared with numerical results and convergence order computed. Results are shown in the table below.

Cell size |

Average Error |

Order |

Simulation |

|---|---|---|---|

\(2\pi/8\) |

\(1.2987\times 10^{-2}\) |

||

\(2\pi/16\) |

\(1.6123\times 10^{-3}\) |

3.01 |

|

\(2\pi/32\) |

\(3.3429\times 10^{-4}\) |

2.26 |

|

\(2\pi/64\) |

\(9.4169\times 10^{-5}\) |

1.82 |

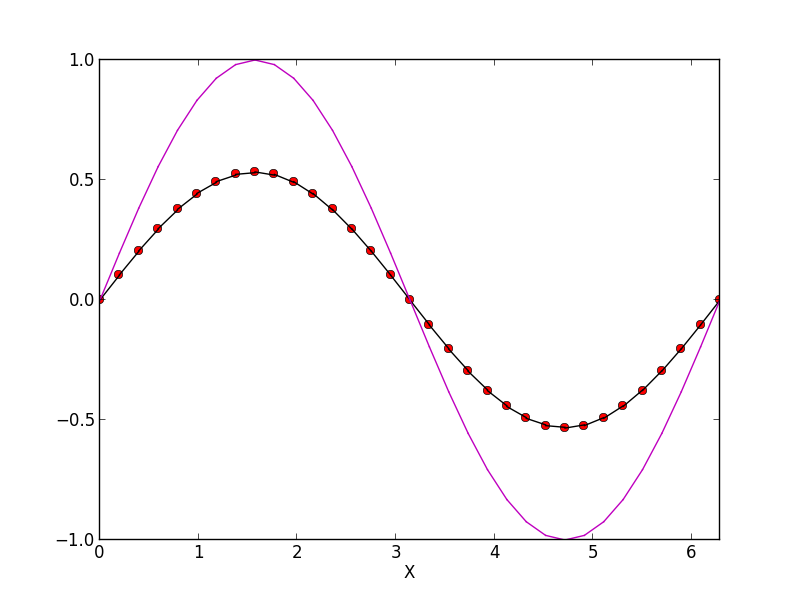

The following figure shows the exact solution compared to numerical results for the 32 cell case.

Advection-diffusion with nodal local DG scheme. Magenta line shows initial conditions, black line numerical results at \(t=2\pi\) and red dots the exact solution. See [s209] for input file.¶

References¶

Cockburn, B and Shu, C W, “The local discontinuous Galerkin method for time-dependent convection-diffusion systems.” SIAM Journal on Numerical Analysis, 35 (6), pg. 2440, 1998.

Arnold, D N and Brezzi, F and Cockburn, B and Marini, L D, “Unified analysis of discontinuous Galerkin methods for elliptic problems”, SIAM Journal on Numerical Analysis, 39 (5), pg. 1749, 2002.