JE15: Studies with a DG electrostatic Vlasov solver¶

In this document I study various standard “text-book” problems with a discontinuous Galerkin algorithm for the solution of the electrostatic Vlasov system. This system is written in Hamiltonian form as

where \(f(x,v,t)\) is the distribution function, \(H(x,v)\) is a Hamiltonian function and where \(\{H,f\}\) is the Poisson bracket operator defined by

The Hamiltonian takes the form

where \(\phi(x,t)\) is a scalar potential and \(q\) and \(m\) are the particle charge and mass respectively.

Two classes of problems will be considered: the first, in which the potential is determined by solving a Poisson equation

where, \(\rho_c\) is the total charge density. In this class of problems the ion distribution function is not evolved: the ions simply provide a neutralizing background to the electron motion. Hence, the charge density is determined from

where \(n_{io}(x)\) is the fixed ion number-density profile, \(e\) is the charge on an electron and \(Z\) the ion charge number.

In the second class of problems the electrons are assumed to be a massless, isothermal fluid. In this case, the electron motion is determined from the condition of quasi-neutrality that, for small deviations, can be written as

where \(n_{eo}\) is the constant electron initial density and \(T_e\) is the fixed electron temperature. This allows the determination of the potential once the ion number density is known.

Notice that in the first class of problems the distribution function for the electrons is evolved, while in the second class of problems the distribution function for the ions is evolved. Hence, they represent the high-frequency (plasma frequency) and low-frequency (ion sound speed) branch of the electrostatic plasma dispersion relation respectively.

Tests for the Vlasov-Poisson system¶

Linear Landau damping¶

In this test the ability of the algorithm to capture the phenomena of Landau damping is shown. For this the electrons are initialized with a perturbed Maxwellian given by

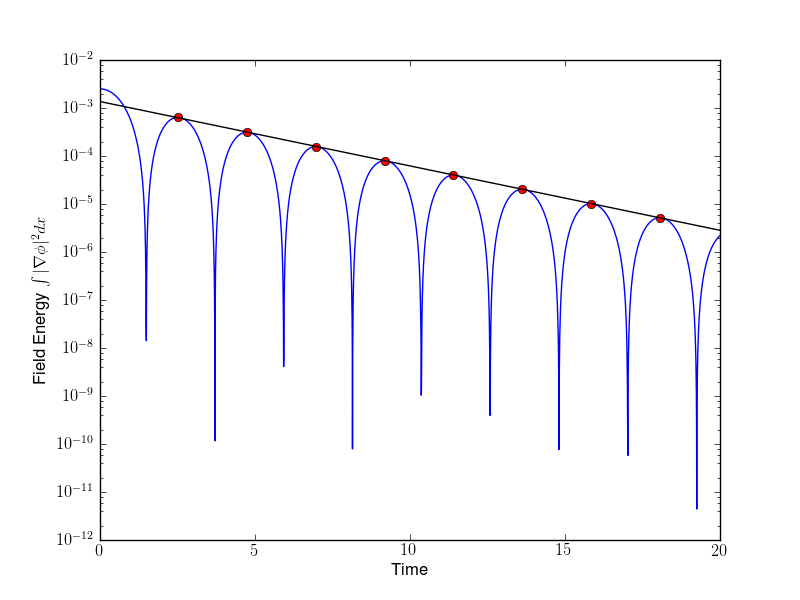

where \(v_t\) is the thermal velocity, \(k\) is the wave-number and \(\alpha\) controls the perturbation. Periodic boundary conditions imposed in the spatial direction and open boundary conditions in the velocity direction. The ion density is set to \(n_i(x) = 1\). For all these tests \(m=1\), \(\epsilon_0=1\), \(Z=1\) and \(\alpha=0.01\). With these settings, the plasma frequency is \(\omega_{pe}=1\) and Debye length is \(\lambda_D = \sqrt{T_e}\). The wave-number is varied and the damping rates computed as the slope of the least-squared line passing through successive maxima of the field energy. See figure for details. An example plot of field energy is shown in the following figure for the case \(T_e=1.0\).

Field energy (blue) as a function of time for linear Landau damping problem with \(k = 0.5\) and \(T_e = 1.0\). The red dots represent the maxima in the field energy which are used to compute a linear least-square fit. The slope of the black line gives the damping rate. See [s151] for the input file.¶

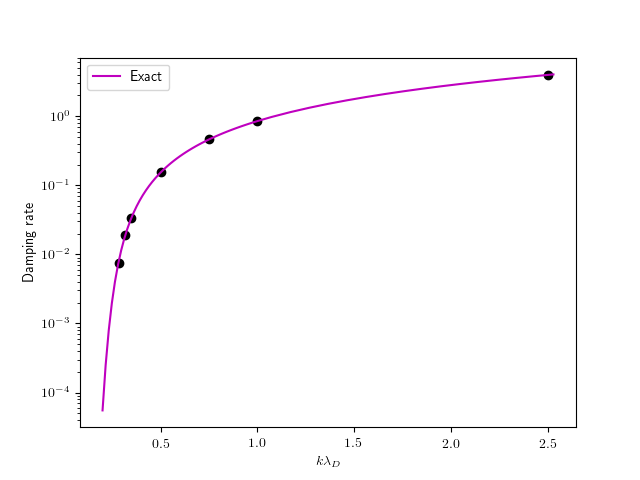

In the following figure the numerical results are compared to the exact values obtained from a numerical root finder that solves the dispersion relation for Langmuir waves. Note that it is difficult to obtain damping rates from simulations with even smaller \(k\lambda_D\) as the numerical damping seems to affect the the delicate damping from the phase-mixing process.

Damping rate from Landau damping for electron plasma oscillations as a function of normalized Debye length. The black dots show the numerical damping rates compared to the exact results (magenta). The damping rates are within 3% of the exact values, and for large values of \(k\lambda_D\) within 1%. agree with the exact results.¶

Nonlinear Landau damping¶

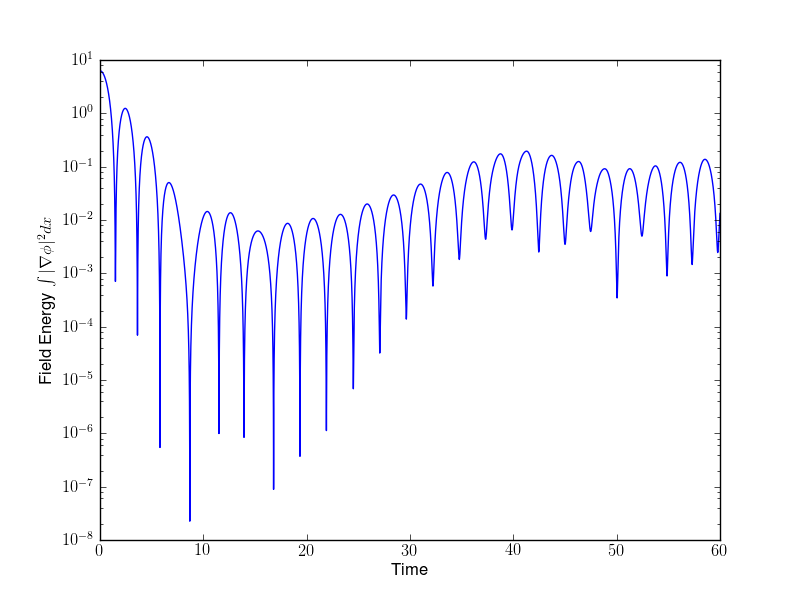

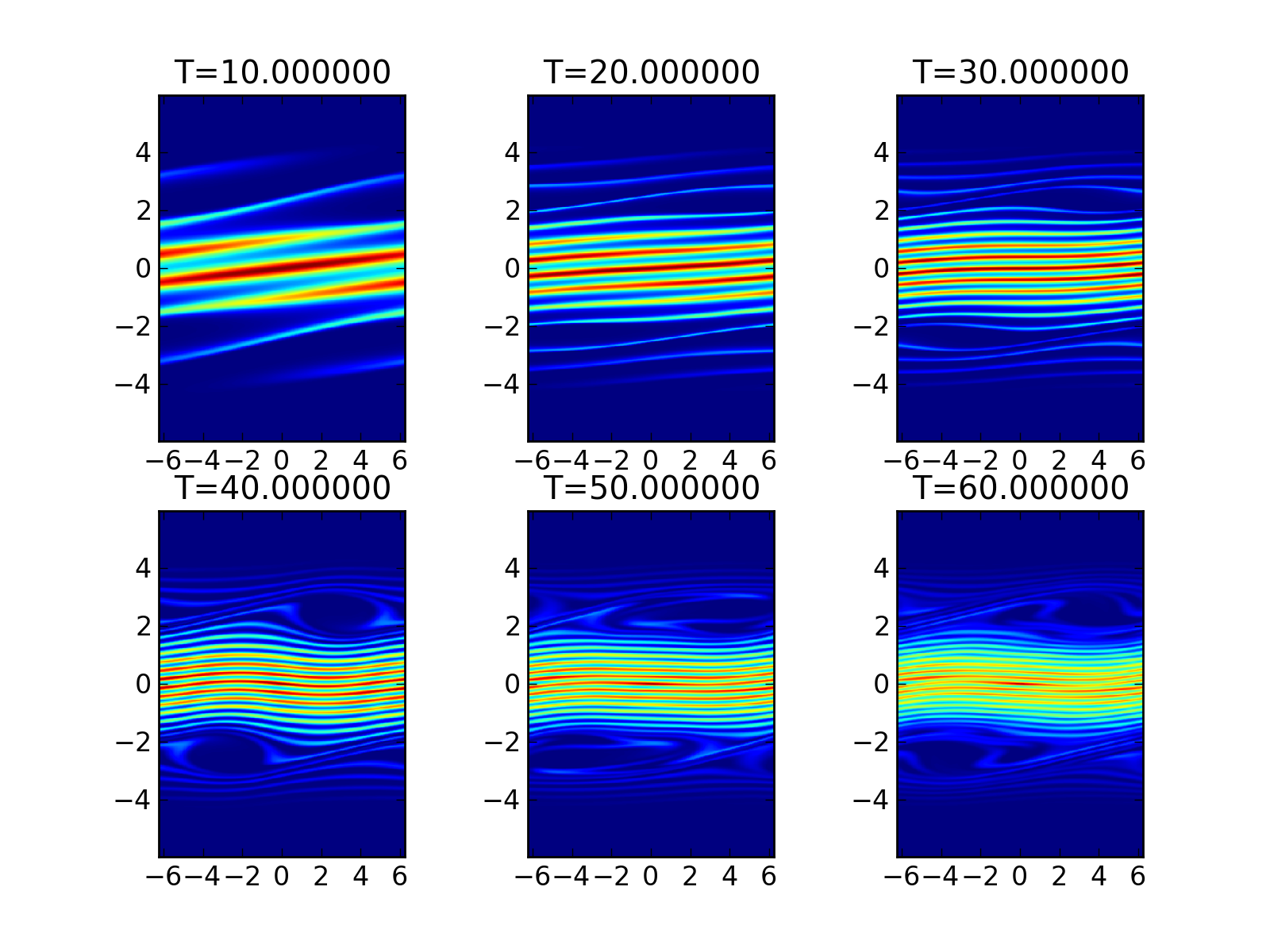

For this problem \(\alpha = 0.5\), rapidly driving the system nonlinear. Other parameters are the same as for the linear Landau damping problem with \(k=0.5\) and \(T_e=1.0\). The field energy history and distribution function at various times are shown in the following figures. Full details of the evolution of the distribution function can be seen in this movie.

Field energy as a function of time for nonlinear Landau damping problem with \(k = 0.5\), \(T_e = 1.0\) and \(\alpha=0.5\). The initial perturbation decays at a rate of \(\gamma = -0.2916\), after which the damping is halted from particle trapping. The growth rate of this phase is \(\gamma = 0.0879\). See [s162] for the input file.¶

Distribution function at different times for the nonlinear Landau damping problem. The initial perturbation undergoes shearing in phase space, leading to Landau damping from the phase mixing (see previous plot for damping rate). Starting at around \(t=20\) the damping is halted due to particle trapping, finally leading to saturation. Phase-space holes are clearly visible.¶

Conservation of Momentum and Energy¶

The Vlasov-Poisson system admits three conservation laws, the conservation of particles, momentum and energy. Taking moments of the Vlasov-Poisson equation leads to the moment equations

where the moments are defined as

Note that the particle energy can also be written as \(\mathcal{E} = mnu^2/2 + p/2\). Integrating the moment equations over space and assuming periodic boundary conditions leads to the conservation laws

where angle brackets indicate spatial averaging. It can be shown that the DG spatial discretization conserves energy.

From the derivation of momentum conservation one can see that a key identity to preserve numerically is

In the continuous case this can be easily derived from the Poisson equation. However, for the discrete case it can be shown that the DG scheme does not preserve this identity. The reason is that although the discrete potential is continuous, its derivative is not. In fact, the error in momentum is proportional to the jump in the derivative of the potential across each interface summed over the domain.

Momentum conservation tests¶

In this series of tests the distribution function is initialized as

where \(\beta_l = 0.75\), \(\beta_r = 0.075\), \(v_d=1.0\), \(T_e=1.0\) and \(x_m=-\pi\). Further, \(f_m(T,v_d)\) is a drifting Maxwellian with a specified temperature and drift velocity. For all problems the domain is \([-2\pi\times 2\pi]\times [-10,10]\) and the velocity grid resolution is held fixed to 128 cells. Spatial resolutions of \(8,16,32,64,128\) are used and relative error in momentum measured.

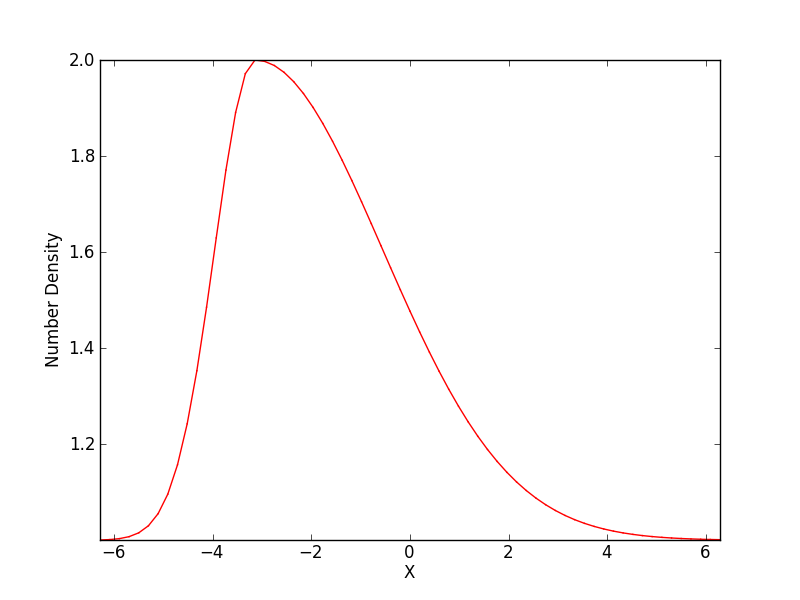

The initial conditions drive strong asymmetric flows around \(x=x_m\) from the asymmetric number density profile. Note that if a symmetric initial profile is used the net initial momentum in the system will be zero and will remain so (to machine precision) as the solution evolves. The initial number density is shown below.

Initial number density profile for momentum conservation test problems. The profile is chosen to drive strong flows resulting in a large initial momentum. See [s183] for the input file.¶

The errors in momentum conservation are very insensitive to the velocity space resolution, as is confirmed numerically. This is not surprising as the momentum is an integrated (over velocity space) quantity and hence the dependence of the error on velocity space resolution is weak.

The following table shows the error in momentum conservation with number of cells. The effective convergence error is also shown. The errors seem to be reducing as \(\Delta x^2\), although at present I am not sure what to make of the fractional convergence rates.

\(N_x\) |

Error |

Order |

Simulation |

|---|---|---|---|

8 |

\(1.3332\times 10^{-3}\) |

||

16 |

\(3.9308\times 10^{-4}\) |

1.76 |

|

32 |

\(8.5969\times 10^{-5}\) |

2.19 |

|

64 |

\(1.5254\times 10^{-5}\) |

2.49 |

|

128 |

\(2.3105\times 10^{-6}\) |

2.72 |

Momentum conservation was also tested using the 3rd order DG scheme. Results are shown in the table below. The 3rd order scheme shows much smaller errors, and even the 16 cell simulation has momentum errors smaller than those of the 128 cell 2nd order simulation. In a certain sense this is not surprising as with piece-wise parabolic basis functions the discontinuity in the gradient of the potential across an interface will be small, leading to smaller errors in momentum.

\(N_x\) |

Error |

Order |

Simulation |

|---|---|---|---|

8 |

\(1.9399\times 10^{-5}\) |

||

16 |

\(4.0001\times 10^{-7}\) |

5.60 |

|

32 |

\(5.1175\times 10^{-8}\) |

2.97 |

|

64 |

\(2.2289\times 10^{-9}\) |

4.52 |

|

128 |

\(8.9154\times 10^{-11}\) |

4.64 |

Energy conservation tests¶

In this series of test the conservation of total energy is tested. For this the same initial conditions and domain size are used as for the momentum tests. A fixed grid of \(16\times 32\) is used and the CFL number is varied. The errors in energy conservation are shown in the following table.

Note that even though the spatial discretization conserves energy exactly, the non-reversible Runge-Kutta time-stepping adds a small amount of diffusion. Thus, the errors in energy should converge to zero with the same order as the time-stepping scheme, in this case third-order. This is clearly seen from the results shown below.

\(CFL\) |

Error |

Order |

Simulation |

|---|---|---|---|

0.3 |

\(1.4185\times 10^{-6}\) |

||

0.15 |

\(1.7687\times 10^{-7}\) |

3.00 |

|

0.075 |

\(2.2078\times 10^{-8}\) |

3.00 |

|

0.0375 |

\(2.7587\times 10^{-9}\) |

3.00 |

Energy conservation was also tested using the 3rd order DG scheme. Results are shown in the table below. As expected, the same third order convergence is obtained as the time-step is reduced.

\(CFL\) |

Error |

Order |

Simulation |

|---|---|---|---|

0.2 |

\(4.1646\times 10^{-7}\) |

||

0.1 |

\(5.1978\times 10^{-8}\) |

3.00 |

|

0.05 |

\(6.4914\times 10^{-9}\) |

3.00 |

|

0.025 |

\(8.1295\times 10^{-10}\) |

3.00 |

Tests for the Vlasov-Quasineutral system¶

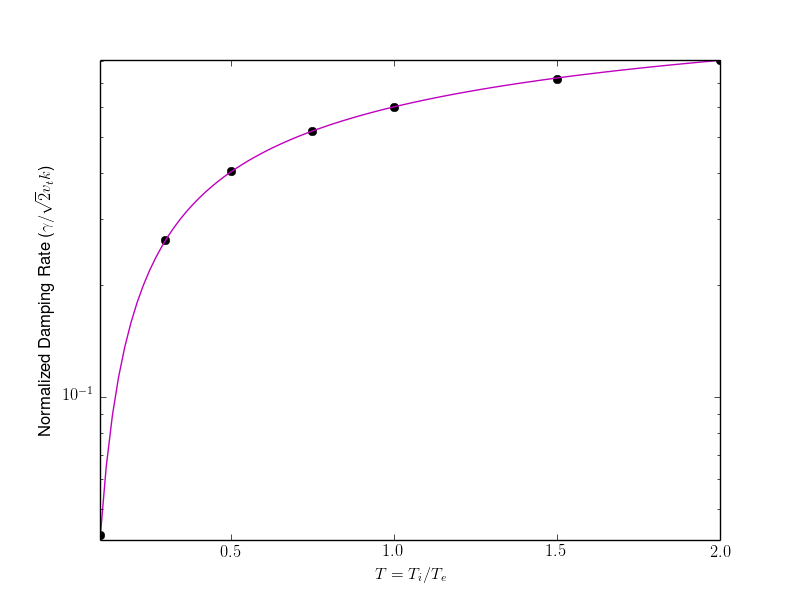

In this series of tests the electrons are assumed to be a massless isothermal fluid. For small deviations the condition of quasineutrality leads to an algebraic expression to determine the electrostatic potential, see (1). In this regime ion sound waves can propagate. However, these waves are strongly Landau damped when the ion and electron temperatures are comparable.

For these series of simulations the ion temperature is held fixed to \(T_i=1\) and vary the ratio \(T \equiv T_i/T_e\). The wave-number is also held fixed to \(k=0.5\). Results are shown in the following figure.

Normalized damping rates \(\gamma/\sqrt{2}v_t k\) where \(v_t = \sqrt{T_i/m_i}\) as a function of temperature ratio \(T_i/T_e\). The black dots show the numerical damping rates compared to the exact results (magenta). Ion sound waves are strongly damped as ion temperature becomes comparable to the electron temperature. Conversely, the damping is very small as the ions get colder.¶

A note on dispersion relations for electrostatic oscillations¶

The plasma dielectric function can be written as

where \(\omega\) is the (complex) frequency, \(k\) the wave number and the sum is over all species in the plasma. The species suseptibilites are defined as

where \(\omega_s = \sqrt{n_sq_s^2/\epsilon_0 m_s}\) is the plasma frequency, \(v_s = \sqrt{T_s/m_s}\) the thermal speed and \(Z(\zeta)\) is the plasma dispersion function. Further, \(q_s\) and \(m_s\) are the species mass and charge respectively and \(T_s\) the temperature.

The plasma dispersion function is defined as

for \(\mathrm{Im}(\zeta) > 0\). The derivative of the plasma dispersion function is given by

Also, \(Z(0) = i\sqrt{\pi}\). In terms of the dielectric function the plasma dispersion relation is obtained from the roots of the equation \(\epsilon(\omega,k) = 0\), i.e, the frequency and wave-number are related by

Plasma oscillations¶

For plasma oscillations it is assumed that the ions are immobile and hence ignore the ion contribution to the dielectric function, leading to the dispersion relation

where \(\lambda_D = v_e/\omega_e\) is the Debye length. Once \(\zeta\) is determined from this equation for a specified \(K \equiv k \lambda_D\), the frequency is determined from \(\omega/\omega_e = \sqrt{2} K \zeta\).

Ion acoustic waves¶

For ion acoustic waves we can express the dispersion function as

where we have now defined \(\zeta \equiv \omega/\sqrt{2} v_i k\) and have assumed massless, isothermal electrons.